culling

As a kid in Hong Kong, one of my favourite cartoons was McDull, a pig who goes on adventures. He is ordinary in many ways, but he has a heart of gold. McDull was born on June 22nd, 1995, the same year I was, the year of the boar.

On November 18th, Hong Kong authorities started killing the city’s wild boar. A week before this decision was made, a wild boar knocked down a police officer and bit his thigh. The boar then fell off the edge of a car park, and plunged ten metres to its death.

The wild boar of Hong Kong are incredible. Traditionally forest animals, wild boar roamed the woods and mountains of Hong Kong long before we came in and started erecting skyscrapers, creating artificial land and light pollution that would cloud their sky. In other words, Hong Kong belonged to the wild boar long before it was our home.

Last September, a group of four wild boars was spotted taking a dip in the fountains outside the Bank of China Tower in Central, Hong Kong. Wild boar have been known to wander into the city streets of Hong Kong. From police stations to malls, airport tarmacs to dumpsters, and even subway cars, these animals are often photographed in “civilized” settings where they do not belong. But how often do we question whether our city streets belonged in these mountains to begin with?

“Cull” is defined, by Merriam-Webster, as a verb, meaning: “to reduce or control the size of something, such as a herd, by removal (as by hunting or slaughter) of especially weak or sick individuals.”

I’ve been thinking about this word for the past few weeks: what it means to “cull” a herd, to mass slaughter a group of animals considered to be weak. The culling of wild boar is not a metaphor; it is a reality. But I cannot help but think of the parallels it holds to the protestors and dissidents of Hong Kong. In reading about the mass killing of boars, I was struck by this photograph. In it, a man dressed in all black with a black mask on his face is being forcefully taken away by several police officers.

At first glance, I thought it was an image of a pro-democracy protestor being arrested. But under the photograph reads the following caption: “animal rights activist protested the new policy in Hong Kong.” Of course, this man is a protestor, and whether the cause is the right to democracy or wild boars’ freedom is irrelevant to authorities. What matters is our silence.

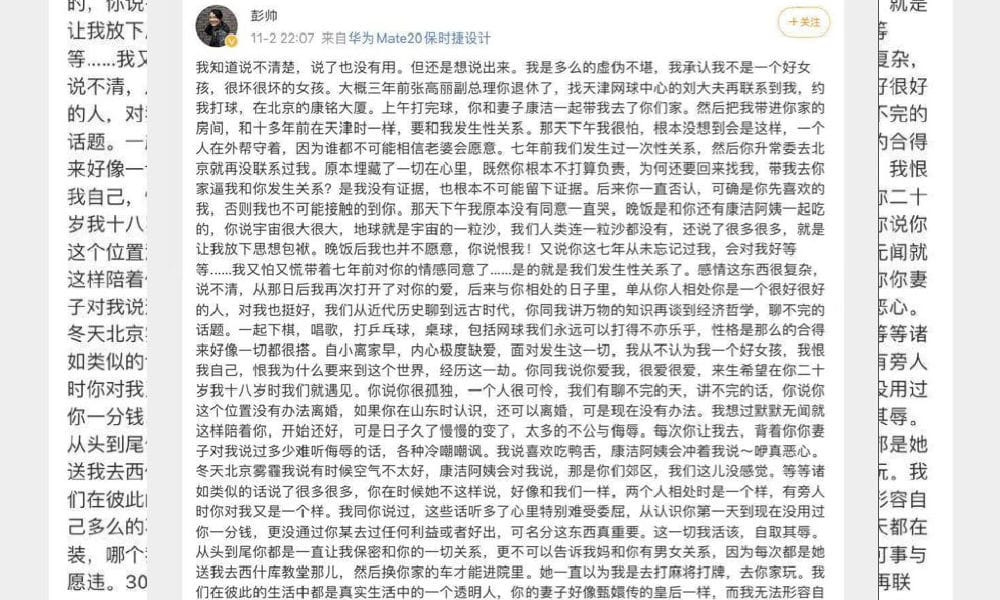

Over a month ago, Chinese tennis player Peng Shuai 彭帥 disappeared. One of the best tennis players in China and the world, Peng Shuai has two women’s doubles Grand Slam titles to her name, and was ranked, in 2013 and 2014, as the No. 1 player in doubles. On November 2nd, Peng Shuai wrote and posted a lengthy post on Weibo, one of China’s approved social media platforms. In it, Peng accuses former Chinese Vice Premier Zhang Gaoli of sexually assaulting her. She details the on-and-off secret affair the two had in the years following. Thirty minutes after she wrote the post, it was taken down, and Peng disappeared from the public view.

In her post, Peng goes into disturbing detail about the sexual assault Zhang Gaoli committed against her, and the events that had occurred since, from seven years ago leading up until the night of November 2nd.

Although the post was taken down by authorities, screenshots had already begun circulating. The full post in Chinese can be read here, and the full translation in English here:

In telling her story, Peng admitted she had no evidence to hold against Zhang. She writes of their affair, which his wife appeared to be completely aware of, and how Zhang’s behaviour towards her in private differed from his public disregard of her. As she writes: “I have no evidence, and it was impossible for any evidence to be left at all. I can’t even describe how unbearable my situation was. Sometimes I wondered if I was still human.”

That Peng Shuai disappeared is not surprising. The man whom she writes about, Zhang Gaoli, served as the senior Vice Premier of the State Council from 2013 to 2018, and was a member of the Chinese Communist Party Politburo Standing Committee, China’s highest ruling council, from 2012 to 2017. In other words, he was very important, and continues to be a symbol of political power, even in retirement.

Power in China is untouchable, unwavering, never humanised. Peng’s accusation not only affects Zhang himself, it also pricks at this image of untouchable authority. The assault and affair Zhang is accused of is grotesque, abusive, and deeply disturbing. Much of it shows the ways in which this flawless image of power is tainted by abuse and desire. To think that those in power, those at the very top, even Xi Jinping himself, could be revealed as human in their desire for power, for sex, and that it could reveal itself in such grotesque ways, is unfathomable, unacceptable to those at the top. And of course, it affects the international image China holds, which affects everything, most acutely the upcoming 2022 Winter Olympics in Beijing.

Two days ago, three more activists were convicted in Hong Kong for their roles in the banned Tiananmen vigil on June 4th, 2020. Jimmy Lai, founder of the disbanded Apple Daily, Gwyneth Ho, activist and former reporter, and Chow Hang-tung, vice chairperson of the disbanded Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements of China, were among the now 24 Hong Kong activists convicted for their involvement in the gathering.

Jimmy Lai was sentenced to 14 months in prison this past April, and now faces additional charges for this conviction. As these activists continue to be punished for their involvement in what was clearly a peaceful, community gathering and mourning, I continually return to this idea of “culling” as a killing off of the weak and sicker populations.

Yesterday, I listened to this 30-minute segment from The New York Times “The Daily" on “The Censoring of Peng Shuai.” In it, they talk about the timeline of events, but also about the nature of Peng Shuai’s silence. Not only was she not listened to, she was also silenced.

Is this what the culling of Hong Kong means? A silencing? I will never think of us, those who fought or are still fighting for freedom, justice, and democracy in Hong Kong, as weak or sick. I do not think getting rid of our physical existence and bodies can remove this “disease” of hope for freedom from our people or home. But I do think the governments have been persistent in their silencing. By censoring our words, our slogans, our art, they effectively find ways to suffocate our voices, put our leaders and heroes behind bars, and find ways to keep them there.

On December 19th, Hong Kong will have its Legislative Council election.

This election, restricted to “patriots only” candidates, include 153 candidates, and is the first since Beijing overhauled Hong Kong’s electoral system this year. This overhaul has made it impossible for pro-democracy candidates to be considered. No traditional opposition parties put forward any candidates this time around. And in response to a fear of a low turnout, Chief Executive Carrie Lam has said:

“There is a saying that when the government is doing well and its credibility is high, the voter turnout will decrease because the people do not have a strong demand to choose different lawmakers to supervise the government. Therefore, I think the turnout rate does not mean anything.”

When I first read this quote, I laughed, and sent it to my friends. Isn’t it absurd? To think that this is the kind of joke that our leaders are using to lead our city and country? It is absurd, but it is also real. The elections on December 19th will come and go and voter turnout will likely be low. And despite what we all know to be the true — that candidates from opposition parties have been disqualified, arrested, or have simply left the city in self-exile — the result is the same: our governing bodies no longer represent us or the people’s best interests. It is funny, it is absurd, and it is heartbreaking.

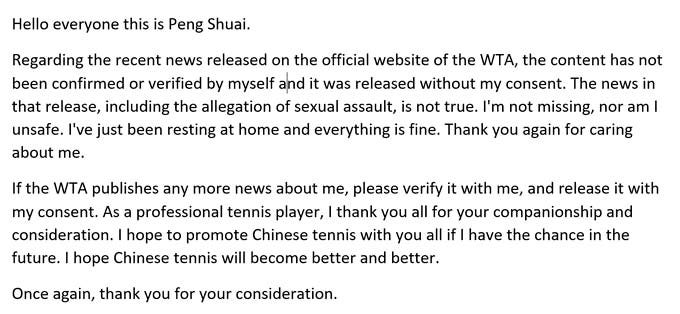

Twelve days after Peng Shuai’s disappearance, the Women’s Tennis Association finally spoke up. Steve Simon, CEO and Chairman of the WTA, released a statement in solidarity with Peng Shuai and demanded the allegations be properly investigated. Multiple major tennis players, including Naomi Osaka, Serena Williams, Roger Federer, Novak Djokovic, and Billie Jean King took to circulating Peng Shuais’ story and the hashtag #WhereIsPengShuai. Five days later, Peng Shuai supposedly wrote an email to the WTA.

The email begins, “Hello everyone this is Peng Shuai.”

If there was ever a way to show that an email was not penned by its supposed author, it is this opening. In Peng’s email, she rescinds her entire post on Weibo and the allegation of sexual assault against Zhang Gaoli. She announces that she is not missing or unsafe. In fact, she has just been resting at home.

Two days later, after the WTA, Amnesty International, and the U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights demanded proof of Peng Shuai’s safety, photos of Peng were released into the pubic. Pictures of Peng eating at a restaurant, attending a kid’s tennis tournament, and later a video of Peng having dinner with her coach and friends announcing the date and time of the video, lest anyone doubt the timestamp, were released.

On November 21st, the International Olympics Committee released a statement of their own, after supposedly speaking to Peng Shuai over a video call. The supposed call they had was suspicious. First, a recording of this call was never shared, and the statement only included a solitary photo of Peng Shuai on the screen. Secondly, of the people included on that video call, there was supposedly a translator there, to aid Peng Shuai with her English. This is particularly strange because Peng Shuai speaks perfectly fine English, and would not have needed such aid.

And then the WTA took a real stance: they decided to suspend all tournaments in China (and Hong Kong), effective immediately. Since then, countries have begun to diplomatically boycott the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics. Countries like the United States, United Kingdom, Australia, and Canada have all decided to do the same. And it sounds exciting, hopeful even — this means the west is finally taking a real risky stance, right? Not exactly.

A diplomatic boycott of the 2022 Winter Olympics in Beijing does not actually mean these countries won’t participate, nor does it mean athletes from those nations will not be attending or competing in the games. What it means is that these countries will not send delegations of government officials to attend the opening and closing ceremonies. That is all.

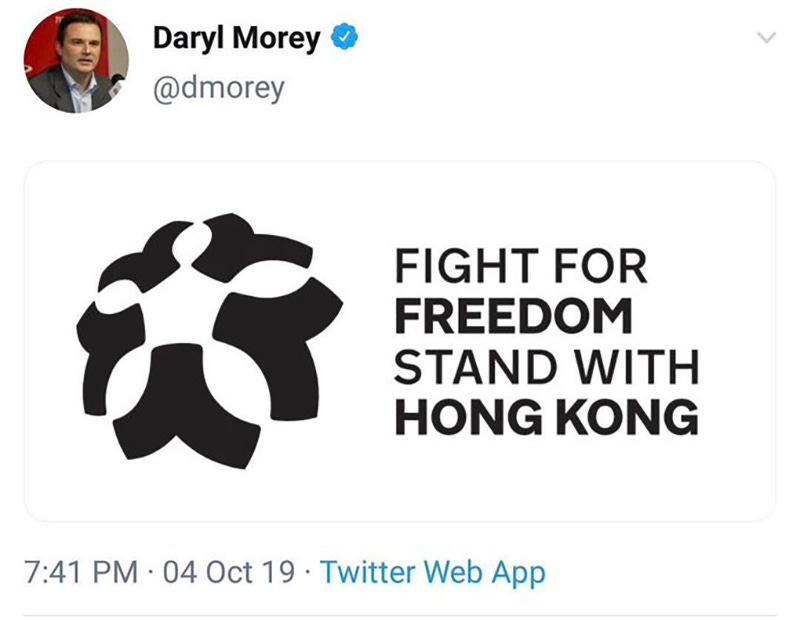

Which brings us back to the WTA and sports as a whole. While the WTA’s suspension of tournaments in China and Hong Kong is bold and indicative of a clear stance, most sports associations and leagues have stayed completely silent. The Association of Tennis Professionals (ATP) has been supportive but stayed relatively silent. Most men’s tennis leagues have stayed silent. It is reminiscent of 2019, when Houston Rockets’ General Manager Daryl Morey tweeted an image in support of the Hong Kong anti-extradition protests, and was denounced by China. Shortly after he released his statement, the NBA apologised for it. No other sports league came to his defense.

Peng Shuai’s bravery and voice scared Chinese authorities, but the fundamental system underneath it all has not changed. The 2022 Olympics will likely take place as planned, with athletes from America, the United Kingdom, Australia, and Canada attending and competing. Everyone wants to make their goodness known. No one wants to risk actual consequences.

The government will continue to try to cull not its people, but our voices, our spirits, our collective spirit. I refuse to believe this can be achieved. You cannot cull what is not weak. You cannot kill what will not die by brute force or silencing.

Since the government’s decision to cull the wild boar of Hong Kong, tens of thousands of people, animal activists and veterinarians, have petitioned against this mass murder of our home’s native animals. It is inhumane, brutish, and unnecessary. And it all started because of one police officer, one man in a position of power, who felt threatened by one wild boar. It all sounds familiar, doesn’t it?

formosa

In this week’s joy, first, of course, my favourite clip of McDull. It is perhaps one of the most well-known clips of McDull, in which McDull goes with his friend to a noodle shop and tries to order fishball noodles. It is funny, fast, and filled with wordplay. In the short 50-second clip, I get such a clear sense of McDull’s naivety, joy, and profound Hong Kong-ness. As an adult, I often turn to McDull when I think of home, when I think of childhood, because it is filled with such joy and the home I grew up with. It has preserved what is now slowly being lost.

And then a Hong Kong Cantopop boy band that one of my closest friends introduced me to. The group, Mirror (or MIRROR) consists of twelve members; Frankie Chan, Alton Wong, Lokman Yeung, Stanley Yau, Anson Kong, Jer Lau, Ian Chan, Anson Lo, Jeremy Lee, Edan Lui, Keung To, and Tiger Yau.

The band’s music is fun and joyous, but most of all, it is infused with Hong Kong.

Mirror has become the city’s hottest boy band, and has filled Hong Kong with the joy and community gathering that had become scarce in the last two years. While Mirror does not actively sing about the political upheaval happening in the city, its songs feel representative of the spirit that has kept so many of us alive and hopeful to this day. As Gwyneth Ho, one of the three activists recently convicted for her involvement in the Tiananmen vigil of 2020, quoted from “Warrior,” one of Mirror’s songs about perseverance: “The worst that could happen is death, and I won’t avoid it.” She said that the first time she cried after her arrest was when she heard this song.

I hope you can find some joy in this music. I still have a lot of hope, and a lot of spirit; in moments like these, I feel myself pulling towards other Hong Kongers who are still fighting. I have faith that as long as we continue to find one another, no amount of silencing can actually cull our collective dreams or memory. Sometimes it feels like the two are one and the same.

Until 2022,

香港人加油!

Parachute 香港人 🇭🇰