fantasy

What is your fantasy Hong Kong? Is this the home you are homesick for?

Dear friends,

When you think of Hong Kong, what does it look like? In your fantasy, what is Hong Kong? What does it look like, smell like, feel like? Who are the people? Who are you? What is the dream version of this city that you imagine returning to, or arriving in, knowing that that place is Hong Kong?

I went to bed early last night, hoping to get a full night’s sleep. Instead, I woke up every hour on the hour. In one of my dreams, I was trying to search for the right way to say something in Spanish – I’ve been taking Spanish II with undergraduates this semester – and I woke up still searching.

Two weeks ago, I called my father, asking if I should come home. I’d been feeling anxious and sad, and had a week off coming up. I wondered if going home would help. When I first came to America in 2009, I was immediately homesick. My mom had helped me purchase a mini Tatung electric cooker, a small cut of Taiwan to keep with me in America, along with canned treasures, like abalone and sardines, that I could eat with white rice when I was homesick. Electric cookers were forbidden in dorms, so I would use it sparingly, often on weekend nights when the other girls were out. One of my most vivid memories of that first year abroad were the hours I spent playing with my online Facebook goldfish in my dorm room across from the bathroom, its door swinging open every once in a while with the sound of a giggle, while my rice steamed, hidden in my closet.

It’s been 14 years since I left Hong Kong. In the many years that I have spent in school, that departure has always felt temporary – eventually, I would end up in Hong Kong, right? Eventually, everyone goes home, right? Isn’t that what the word home means?

The word for home means something different in most languages. In French, there is no direct word known as “home.” The physical structure of a house is “une maison,” an apartment “un appartament,” and if I were to talk about my home, “chez moi,” meaning, “the home of me.” In Spanish, similar rules apply; the sentiment of “chez moi” translates to “mi casa.” In both Romantic languages, home stays with a person, or refers to a physical structure. But in Chinese, the word for home is in direct reference to family, or that which holds ownership of something.

The word 家 has evolved over thousands of years. What began as a carving on a bone of an animal under a roof has since transformed into what we know pronounce as “jia” (Mandarin) or “ga” (Cantonese).

On its own, the word 家 means home. But it also means family:

As in 家庭 (transliteration: home court)

As in 家人 (family members; transliteration: home person)

As in 國家 (country; transliteration: nation home)

As in 作家 (writer; transliteration: make home)

This recent bout of homesickness had come too soon. I had just been home this past December; those of us who live away from Hong Kong know three months was too soon. So I started to dream.

I’ve spent the last few weeks pondering the questions I started this letter with – what is my fantasy Hong Kong?

What started off as a homesickness in 2009 could be cured with brief uses of my Tatung electric cooker and flights home. But soon it turned into a homesickness that could not be relieved by the city itself. Home had changed. Is this what it feels like to be sick for a place that is not home?

During my bout of homesickness, I attended a screening of a 2022 Hong Kong film, 憂鬱之島 Blue Island, a documentary by filmmaker Chan Tze-Woon. Over the last few years, I’ve followed and seen almost every Hong Kong documentary released – and often, banned. I walked into the screening expecting it to replay what many documentaries about Hong Kong tend to cover, the history, courage, brutality, and grief of the 2019 protests. But instead, I witnessed and experienced one of the most beautiful films I’ve had the privilege of watching.

Chan was present at the screening and spoke about his work. He started making Blue Island in 2017, after the Umbrella Movement, and before the anti-extradition protests. The film is playful, weaving in past and present timelines, mixing genres within documentary making. Chan works with activists from past movements, including the riots of 1966 and 1967, the Tiananmen student protests of 1989, and even those who first fled to Hong Kong via water in the 1940s and 1950s. And he recreates those stories using activists and protestors from the 2019 protests. These protestors are not professional actors, but in this film, they stand in as such. They re-enact these historical moments and stories, and then come together with those of the previous generations in dialogue to talk about what it means, to have participated in such different movements across the decades, in the very same place, in their home: Hong Kong.

The city has changed, keeps changing, has never stopped changing. In every generation, there is something people are fighting for: the right to be patriotic to China, or the right not to be; the right to free speech and a better Hong Kong, or a Hong Kong that will preserve its own history instead of succumbing to capitalistic expansion. In every version of Hong Kong, there is a fantasy that cannot be fulfilled.

I’ve spent the last many weeks compiling images, sounds, and smells of my fantasy Hong Kong – a beast that I’ve only recently started to admit might not be realisable, might not even be desirable beyond my yearning for a previous Hong Kong I’ll never get to experience.

What is your fantasy Hong Kong? What does it look like? Smell like? Feel like? Sound like? Where do you fit in it? Why is this the fantasy? Is this the home you are sick for? Tell me what yours is in a comment or a message, I’d love to know.

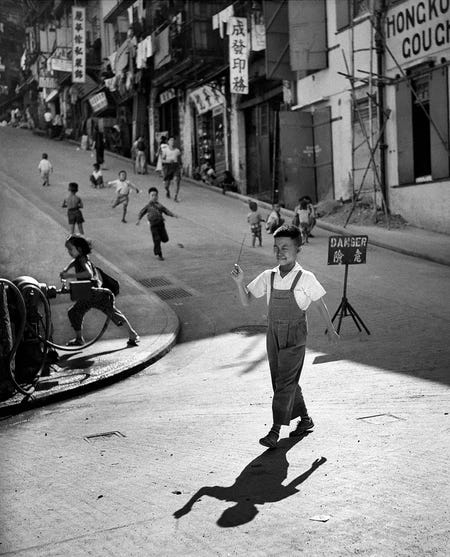

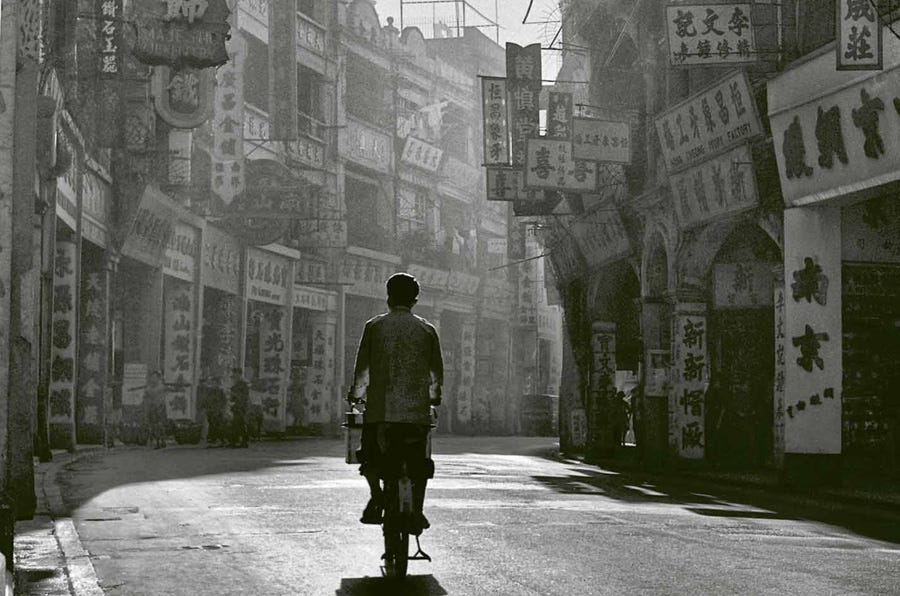

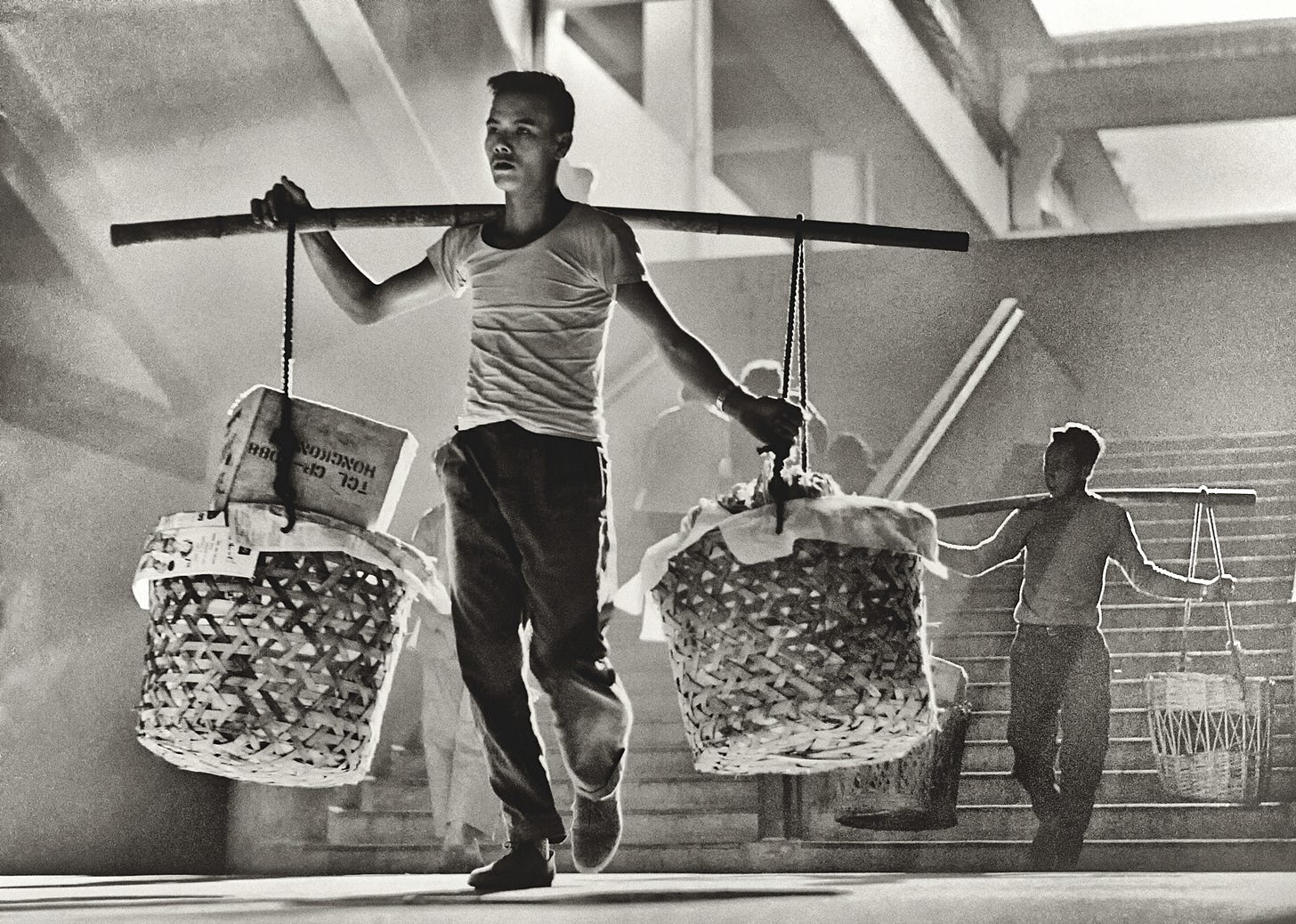

in today’s formosa, I’d like to leave you all with the images I’ve so loved of Hong Kong, beginning with iconic Hong Kong photographer Fan Ho’s work from the 1950s and 1960s.

All of Fan Ho’s work is incredible – much of it captures a Hong Kong I yearn to have seen and experienced. Many of the places he photographed are places I recognise but which are changed beyond compare. And as we move forward in the decades, from the 70s –

To the 80s, with much of Greg Girard’s work –

And 90s (also Greg Girard) –

In one of my fantasy Hong Kong days, I am in primary four and just taking the MTR for the first time on my own. I’ve had too much bubble tea but the streets smell of fresh-off-the-iron 雞蛋仔 (eggies) and 蛋撻 (egg tarts), which still only cost two Hong Kong dollars. TVB is playing the best shows from the mid-2000s, like 我的野蠻奶奶 (War Of In-Laws) and everyone is laughing. Every day, we watch the news in the morning but only to hear the weather report. Every day it says it will rain but every day it doesn’t. Every day in my fantasy Hong Kong, I’m at home.

Until next time –

Parachute 香港人

Your writing resonates with me, almost uncannily expressing my feelings when I felt not-at-home with anything around me or even my own identity/body.

Just wanna let you know your writing has power and I really enjoy every piece of it. Keep writing and I hope to read more.

Receiving your writing today has made my day.

Love from Taiwan.